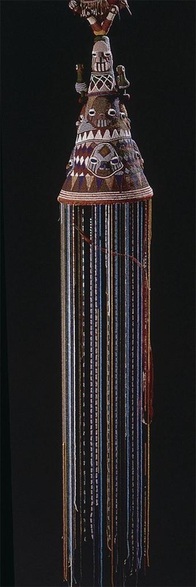

Adenla Crowns.

This crown used to symbolize royalty in the Yoruba culture is said to have power of its own. These crowns symbolized the hereditary right that the Oba’s have to rule and it’s the greatest mark for them. In the past the Oba’s were based on lineage but now they are chosen from royal families by a group called the king-makers.[1] These crowns were embroidered with beads. Strands of beads were used to create patterns and shapes on the top part of the crown. Both a mixture of African-made and

European-made beads can be used to adorn these crowns.[2] The crowns also contained veils that were used to cover the face. These veils are not meant to cover the face so that you cannot see it, but more of a cover or mask that allows the Oba to fade from a person to the deity. The veil helps take away any defining features that the Oba has.

[1] Douglas Fraser, "The Symbols of Ashanti Kingship," African Art & Leadership, ed. Douglas Fraser and Herbert M. Cole (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1972), 209-211, 227-238.[2] Peri M. Klemm, "African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment," African Arts, 44.3 (2011): 91.

Beadwork: Adenla (beaded crown), Beadwork, (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

[1] Douglas Fraser, "The Symbols of Ashanti Kingship," African Art & Leadership, ed. Douglas Fraser and Herbert M. Cole (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1972), 209-211, 227-238.[2] Peri M. Klemm, "African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment," African Arts, 44.3 (2011): 91.

Beadwork: Adenla (beaded crown), Beadwork, (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

Egungun Masks.

Leadership comes in several different forms. While the Egungun masks do not represent a certain leader or person, they can be looked towards for guidance. The Yoruba from Nigeria use these masquerades and incorporate music, dance, poetry and art to create a way to connect with their ancestors. Connections with recently deceased ancestors allow the ancestor to make sure everything is ok and that they are able to move on into the spiritual world.[1] Another example of guidance is with the use of masks that look like foreigners or Europeans. These masks interact with each other and show the Yoruba how not to act in public. After the performance of the European masks, another set of Egungun masks come through and then show the Yoruba how to act properly in society. These Egungun masks are created from cloth using patchwork. They extend and cover the entire body so that all of the spiritual power will be held within them. The headdresses can be made of either wood, cloth or the combination of both.[2]

Satirical Egungun: European Couple Ilogbo, Awori, Nigeria, 1982, (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

[1] Monica Blackmun Visonà, Robin Poynor, and Herbert M. Cole, A History of Art in Africa, (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008), 253.

[2] Visonà, page 159.

Satirical Egungun: European Couple Ilogbo, Awori, Nigeria, 1982, (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

[1] Monica Blackmun Visonà, Robin Poynor, and Herbert M. Cole, A History of Art in Africa, (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008), 253.

[2] Visonà, page 159.

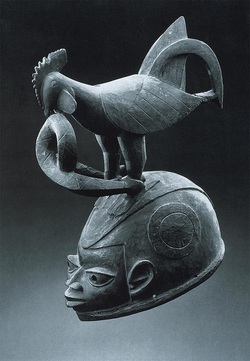

Gelede Masks.

This and other Gelede masks are used in masquerades by the Yoruba people. Their significance is to honor women whether they are ancestors, deities or still living. In the Yoruba culture it is said that women have a special power or force within them that manifests through behavior whether it be good or bad. This is a feared spiritual power of women. This force can affect individuals or whole communities.[1] The Gelede was a sort of cult for women. While the actual dances were danced by men either in public or private, the head woman or leader of the Gelede was allowed to enter the room to see and help with the masquerades. The Gelede cult is responsible for worshipping their women ancestors so that they may give good blessings and help with fertility among the Yoruba women. Costumes are very elaborate and are made of carved wood. They will often incorporate some sort of cloth that covers the dancer’s face but does not necessarily conceal it.[2]

Mask: Gelede, possibly by the carver Duga of Meko South-western Nigeria, 20th Century, wood, h.37.5cm, (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

[1] Roslyn Walker, African Women/African Art, (New York: The African American Institute, 1976),

[2] Monica Blackmun Visonà, Robin Poynor, and Herbert M. Cole, A History of Art in Africa, (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008), 254-255.

Mask: Gelede, possibly by the carver Duga of Meko South-western Nigeria, 20th Century, wood, h.37.5cm, (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

[1] Roslyn Walker, African Women/African Art, (New York: The African American Institute, 1976),

[2] Monica Blackmun Visonà, Robin Poynor, and Herbert M. Cole, A History of Art in Africa, (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008), 254-255.